The History of English Dubbing in Rome

For my very first post on this blog, I’m going to try to dig into the history of the English dubbing scene in Rome. Now, if you think that sounds overly ambitious, then you’re right! A comprehensive history of English dubbing in Rome cannot be told in a mere blog post. I am, however, going to do my best to at least get the basics covered by tracing the industry back to its humble origins and taking a closer look at how it expanded, the working methods, some of the biggest challenges faced by the dubbers, the dubbing organization ELDA, and some of the key players – hopefully, in a way that will provide interested readers with a good understanding of how English dubbing in Rome worked back in the golden years of the 1960s and 70s.

Before we can fully delve into the history of English language dubbing in Rome, however, it is necessary to first a closer look at the Italian language dubbing practices of the time and their origins.

Italian dubbing traditions

Italy is one of the world’s best known dubbing countries, and the practice of dubbing all foreign films into Italian dates back all the way to the introduction of sound cinema with The Jazz Singer in 1927. In Italy, the use of subtitles was never even in question due to the large percentage of illiteracy in the population at that time, and so dubbing was a natural choice. The early imported American talkies were actually dubbed into Italian in America by the Hollywood studios themselves, who employed Italian-American actors to do the dubbing, but the results were highly unsatisfactory due to the dubbers’ strong American accents.

Thus, in the early 1930s, the first dubbing studios were set up in Italy, where more authentic-sounding Italian dubs could be created by native speakers. The one who really cemented dubbing’s position in Italy, however, was Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, who banned the use of foreign language in films, and prohibited the screening of any foreign films that had been dubbed into Italian abroad. Consequently, dubbing into Italian could only happen in Italy, which allowed Mussolini to actively use dubbing as a tool for manipulating foreign films to push his own ideological agenda. Any dialogue containing unflattering references to Italy or Italians was promptly removed, and any plot points considered morally undesirable were censored by altering the dialogue.

In the post-war years, Italy broke free from the totalitarianism of the Mussolini era, but dubbing remained as movie-goers had become accustomed to watching foreign films dubbed into Italian. A preference which continues to this day, with only a very few select cinemas in Rome presenting foreign films in their original language with subtitles.

|

| Italian dubbers at work. |

But while the long-standing Italian tradition for dubbing foreign films is widely known, far fewer movie viewers are aware that Italian filmmakers also have long tradition of also dubbing their own films, with even some of the country’s biggest stars, such as Sophia Loren and Claudia Cardinale, having frequently had their voices dubbed over by others. This practice, too, dates back to the Fascist era, and originated because of the wide range of different Italian dialects and accents. Mussolini’s strict regulations prohibited not only the use of foreign language in films, but also all dialectal forms. The Fascists sought to stop people in different regions from speaking local dialects, and saw cinema as a useful tool for unifying Italians in the use of one conservative and ‘pure’ national language. All Italian films were thus dubbed into standardized Italian by experienced theater actors speaking with perfect diction, free of any sort of regional inflections.

The end of WW2 meant the end to these strict regulations on dubbing, but the practice of completely post-syncing all Italian films continued nonetheless. Partly because the tradition had become so familiar and well-established, but equally so out of necessity. For starters, much of the technical equipment available at the time was basically war surplus, with cameras that were so noisy it was more or less impossible to record live sound. Secondly, the neorealist directors preferred casting their films with non-professional actors they found on the streets. Most of these people knew nothing about how to recite lines, and their poor diction and broad regional dialects were so incomprehensible to general Italian movie-goers that it was necessary to have them dubbed by professional actors.

And last, but certainly not least, dubbing continued because of Italy’s growing reliance on the co-production system – that is, production companies from different countries joining forces to make a film together. Italian filmmakers primarily entered into co-productions with France, Spain and West Germany, and these deals were lucrative because it allowed the productions to pool resources and receive grants and tax reliefs from multiple governments.

However, this also meant that the various co-production countries would insist on having their own stars featured in prominent roles, which then resulted in casts made up of a number of different nationalities. Many of these actors were unable to communicate with each other as they could not speak any other languages than their own, and thus the various actors would recite their lines in their native tongues. With the movie sets turning into a veritable Babel’s tower of different languages, recording live audio was out of the question, and instead the films were shot silent, with the entire soundtrack put together in post-production.

For the Italian filmmakers, shooting without sound offered a number of advantages, as scenes could be shot more quickly, with fewer takes and without having to wait for ideal sound conditions etc. And if an actor fluffed a line, it didn’t matter – he could just keep going, and if the director liked the take, he would use it, safe in the knowledge that everything would be fixed in the dubbing later on. Furthermore, the filmmakers were able to cast largely on appearance. If an actor was attractive but didn’t have a ‘good’ voice, or had bad diction, it didn’t matter, because a more appealing voice to fit the face could easily be found.

Even a lot of big stars had their voices dubbed over, typically because their regional accents were considered too broad for most Italians to understand. One big Italian star whose voice was routinely dubbed was Claudia Cardinale. Although Cardinale’s parents were Italian, she was born and grew up in Tunisia, which was then a protectorate of France. Her first language was therefore French, and she spoke Italian with a distinct French accent which the film producers felt was distracting. Furthermore, Cardinale’s unique throaty voice was considered much too husky, and so she was dubbed in nearly all of her early films. It wasn’t until in the 1970s that she began to dub her own voice in Italian.

|

| Claudia Cardinale was one of the great Italian stars to be routinely dubbed. |

Other times, actors were dubbed because their regional accents might prove to be a source of unintended humor. “In Italy, you simply couldn’t play a serious role with a heavy Neapolitan accent. Everyone would laugh,” English dubbing actor/director Ted Rusoff explained in a 1975 newspaper article on dubbing.

And so the tradition of dubbing Italian films carried on for decades, but the practice eventually tapered down considerably as on-set recording technology improved over the years. It still occurs, though mainly in the case of non-Italian actors. Interestingly, even though the strict regulations from the Mussolini era are of course long gone, the use perfect diction and standard Italian pronunciation has managed to endure, and continues to be the norm in Italian dubbing.

The early days of English dubbing in Rome

Having delved a bit deeper into the traditions of Italian dubbing, it is time to move on to the history of English dubbing in Rome. Unfortunately, very little has been written about how the industry first got started, and what has been written seems to frequently be based around assumptions. One of the more popular misconceptions is that English dubbing in Rome started up in the late 1950s and then expanded in the wake of the great international success of the peplum spectacle Hercules (1958), starring Steve Reeves. And while it is certainly true that the success of Hercules resulted in an avalanche of further sword and sandal adventures, and that this, in turn, led to the birth of the spaghetti western and Eurospy films – all of which kept the English dubbers extremely busy throughout the 1960s – the truth is that the English dubbing scene in Rome was already well established by the time Hercules was rolled out.

In fact, its meager beginnings can be traced back all the way to the late 1940s, and at the forefront was a brilliant bilingual lady by the name of Gisella Mathews. In 1947, Mathews was employed by Eagle-Lion Productions in Rome, translating American films into Italian for dubbing, when she was approached about whether she’d be interested in trying to dub an Italian film into English. The film in question was Alessandro Blasetti’s drama-comedy Four Steps in the Clouds (1942), a notable success when originally released in Italy, and which the producers were seeking to profit further from by exporting it to English-speaking markets. Mathews agreed, and Four Steps in the Clouds became one of the first films to be dubbed into English in Rome.

In America, Italian films had up until this point mostly been shown in subtitled form in niche art cinemas only, but now more and more producers were starting to wake up to the potential gains in taking Italian films out of the art cinemas and reaching a larger audience – with dubbing seen as the tool to achieve this.

Establishing an English language dubbing industry in Rome was no easy task, however, as there were not many American or English actors based there at the end of the 1940s, and the ones that were there had no experience with dubbing. Instrumental in getting it all up and running was actually an Italian theater actor by the name of Valentino Bruchi. Bruchi’s mother was originally from England, and he was therefore a natural bilingual, and more importantly, he was experienced in the field of dubbing, having been involved with Italian language dubbing ever since the early 1930s. Under Bruchi’s guidance, the first English dubbers in Rome learned their trade, and the English dubbing scene slowly began to take shape.

“It was on that occasion that I gave birth to English-language dubbing, which has since developed, through the years, into a thriving business,” Bruchi wrote in his autobiography Passeggiate nel tempo (tra ceroni e microfoni) (published post-humorously in 2009, but originally written in 1977). “I created it from nothing, and my dubbers were American ex-servicemen who had remained in Rome to study. It was no small effort, because I was dealing with people who did not even know what dubbing was. Then, little by little, it developed and professional actors who wanted to spend some time in Italy began to arrive. Many of them settled there permanently” (translation mine).

Soon, Gisella Mathews was receiving more offers from other companies, and in October 1949, she and Valentino Bruchi founded the Anglo-American Dubbing Association, a non-profit organization set up to provide English voices for the dubbing of Italian films. Originally, there was a stable of just 12 actors available to dub voices, but already by 1953, this had increased to around 60 dubbing actors. |

| English dubbing pioneers Gisella Mathews and Valentino Bruchi. |

Central to making the English dubbing scene in Rome possible at that time were two very convenient factors. Firstly, the well-established Italian dubbing industry meant that all of the technical equipment and studios needed to dub were readily available in Rome. And secondly, this was just at the start of the so-called ‘Hollywood on the Tiber’ era, during which Rome emerged as a major location for large-scale American productions. Black Magic (1949), starring Orson Welles and Raymond Burr, was being produced in Rome in the late 1940s, and was soon followed by the immense spectacle of Quo Vadis (1951), which meant the city was buzzing with hopeful English-speaking talent and wannabe actors who could be recruited as dubbers. This, combined with the English dubbers’ ability to work quickly and effectively, were instrumental in establishing dubbing in Rome as a viable option to doing the dubbing in the US.

Unfortunately, trying to piece together a more comprehensive history on English dubbing in Rome in the 1950s is a frustrating and challenging task, because not only is there a distinct lack of information available on the subject, but even the films themselves are for the most part impossible to find in their English-dubbed versions. Camillo Mastrocinque’s melodrama The Fighting Men (1950), Pietro Germi’s crime film Four Ways Out (1951), Alessandro Blasetti’s anthology film Times Gone By (1952) and Roberto Rossellini’s famous neorealist drama Europe ’51 (1952) are among the very few Italian films from the early 1950s that are currently circulating in their English-dubbed versions.

From later in the decade, there are a couple of pre-Hercules peplums for which the English dubs still survive – most notably the expensive Dino De Laurentiis and Carlo Ponti production Ulysses (1954), starring Kirk Douglas and Silvana Mangano, but also a small selection of further costume adventures such as The Queen of Babylon (1954), The Mysterious Swordsman (1956), The Violent Patriot (1956) and The Mighty Crusaders (1957). For the most part, however, English dubs of Italian 1950s films are practically impossible to find, and given the overall lack of interest in older Italian cinema and the general attitudes towards English dubbing, this is unlikely to change any time soon.

Of the dubbing personnel from that era, special mention must be given to the four legendary dubbing director/actors Tony La Penna, Richard McNamara, Lewis E. Ciannelli and George Higgins, all of whom were instrumental in building up the English dubbing scene almost from scratch together with Valentino Bruchi and Gisella Mathews. Six absolute pioneers, most of whom would go on to spend the rest of their lives working with dubbing – standing as central pillars of the Roman dubbing world for some 40 to 50 years.

Among the dubbing actors active at some point during the 1950s (several of whom would continue to work into the 1960s, and in a few cases, far beyond) were Michael Tor, Stephen Garrett, Peggy Nelson, Frank Gregory, Sebastian Cabot, Charles Fawcett, Alan Furlan, Paul Campbell, Frank Latimore, Cindy Ames, Eugene Gervasi, Patrick Crean, Adam Genette, Lisa Figus, Rex Benedict, Ruth Carter, Angela Mantley, Gertrude Flynn, Patricia Browning, John Stacy, George Gonneau, Lee Kresel, Geraldine Catalano, Bill Kiehl, Nona Medici, Jim Dolen, Marie Baxa, Elena Doria, Mary Bourke, Alfred Brown, Richard Camp, John Myhers, Leslie Breidenthal, Julie Gibson, Pamela Matthews, Addison Myers, Harriet Medin, Theodora FitzGibbon, Nina Golding (later known as Nina Rootes) and Michael Billingsley. Even Lois Maxwell (eternally known for her role as Miss Moneypenny in the James Bond films) did some dubbing work while living in Italy for a few years early in their careers.

|

| Dubbing old-timers Bill Kiehl, Stephen Garrett, Nina Rootes, George Higgins and Michael Billingsley at a party, circa 1959. Picture taken from Nina Rootes' book Adventures in the Movie Biz. |

As previously mentioned, the release of Hercules in 1958 turned into such a great success that internationally aimed Italian filmmaking – and, in effect, English dubbing – took off like a rocket. However, the English dub of Hercules that had been prepared in Rome, with Steve Reeves’ voice dubbed by Richard McNamara, did not meet with the approval of Joseph E. Levine, the film’s American distributor. In fact, Levine had the film re-dubbed at Titra Studios in New York, and this was not the only time an Italian import was to meet such a fate.

One of the major importers of Italian productions in those days was American International Pictures (AIP), who began to buy American distribution rights to Italian films in 1959, and who would go on to release a long line of Italian peplum, horror and Eurospy films in the US. One of AIP’s early Italian pickups was Mario Bava’s landmark gothic horror film The Mask of Satan (1960), for which an English-language dub had already been prepared for export in Rome under the direction of George Higgins. But – as in the case with Hercules – AIP were not happy with the overall quality of this dub, and consequently, an all-new dub was recorded at Titra Studios in New York. The film was also slightly cut and given a new score before being unleashed on American audiences under the title of Black Sunday.

This version proved to be a profitable hit for AIP, but concerns over the quality of the Roman-made dubs led to AIP setting up their own dubbing company in Rome to produce English versions of the Italian films they had bought (as well as many of their Japanese imports). Ted Rusoff, the nephew of AIP honcho Samuel Z. Arkoff, was tasked with going to Rome to oversee the quality of the dubbing, and ended up becoming one of the biggest names in the business.

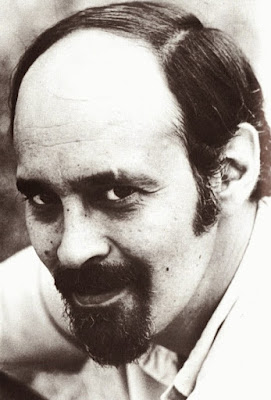

|

| Ted Rusoff (1939-2013). |

The 1960s were truly the golden years of English dubbing in Rome, with practically everything the Italians churned out getting dubbed into English – even stuff you’d never think would have a chance of getting picked up anywhere, like some of the Franco and Ciccio comedies, were given English dubs, because as long as a film had a dub, there was always the chance it might get picked up for US distribution. And a great many dubbed Italian quickies did indeed make their way to American shores. Some made it into theaters, but the main market for these films was actually US television. At the time, a lot of new television stations were being launched, and because they didn’t yet have enough product, they were importing European films en-masse. Throughout the 1960s, hundreds of low-budget Italian, French, German etc genre films films were dubbed into English each year – not only in Rome, but also in Paris – and many of them ended up becoming cherished cult movie favorites thanks to frequent airings on American late-night television.

Interestingly, it was not only in English-speaking territories that the availability of an English dub was needed to secure distribution. A lot of Italian films that never found their way to the US or the UK, instead ended up getting video releases in such places as the Netherlands, Greece, the Scandinavian countries, Brazil and Japan – all territories with traditions for using subtitles instead of dubbing – and, as anyone old enough to have been collecting and trading Euro cult films in the pre-DVD and BluRay era will no doubt remember, these subtitled releases always carried the English-dubbed versions. This was not because English was necessarily more understandable to the movie audiences in these countries, but because it was important to try to uphold the illusion that these were genuine English language productions. They simply would not have been as marketable had they been in Italian.

The dubbing process – from adaptation to recording

The process of dubbing a film from Italian into English could be a demanding and sometimes tedious affair that required a great deal of technical skill, creative sensitivity and precise execution. Usually, when we speak of dubbing, we refer to the sessions in the recording studio, in which words of dialogue are replaced with other words, in a different language, but the process actually begins with the translation of the original Italian dialogue into English. A rather complicated task, because when dubbing from Italian into English, one cannot employ a literal word-for-word translation. Instead, the Italian dialogue must be adapted into English, so that each word aligns as closely as possible with the mouth movements of the actors on the screen – a process known as lip syncing.

One of the most

frequent challenges the dubbing adaptor is faced with when doing this work is the fact that in English, words typically end with a

consonant (mouth closed), whereas in Italian, they tend to end in a vowel

(mouth open). Close-mouth sounds such as b’s, f’s, m’s and v’s are known as

labials, which are crucial to pay close attention to. When adapting the

dialogue from Italian to English, the labials must be retained in the same

places, or else the dialogue is not going to sync up convincingly.

Dubbing writer/director Ted Rusoff, when interviewed for Video Watchdog in 2010, detailed of some of the challenges involved in translating and syncing dialogue: “The bane of every adaptor’s life is the Italian word basta, usually yelled with a great big obvious ‘b’ on the lips. It means ‘enough’, and that word simply won’t fit. By the ‘70s, we were able to get away with vulgarities such as (when it made sense) ‘bastard’. Comedies were a hundred times worse, and I never struggled so much as when there was that long series of sexy Italian comedies, usually starring Edwige Fenech and Lino Banfi.”

|

| The sex comedies of Edwige Fenech and Lino Banfi were a chore to dub |

At the same time, the intent and meaning of the original Italian dialogue must also be respected, thus requiring a great deal of linguistic creativity from the dubbing adaptor as he walks a constant tightrope between changing the dialogue to match the expressions and lip patterns of the on-screen actors, and remaining faithful to the Italian script. Dubbing adaptor/director Gene Luotto, when interviewed by Variety in 1979, referred to the process as inventing a new language which he christened dubbingese, commenting that: “Unlike Italians, Americans insist on lip sync, so you have to go through all sorts of gymnastics to achieve that.”

If the adaptors got too creative in order to achieve perfect sync, however, then that resulted in yet another problem, as pointed out by dubbing adaptor David Mills when he was interviewed by Sun Journal in 1984: “[I]f you just listen to the (dubbed) dialogue itself, you’ll hear there’s a great many strange constructions, people are saying odd things that don’t strike you as being terribly the way people actually talk, merely to fit that mouth movement. That’s the battle you always have in writing. That is, how much good English sense should I sacrifice to make it look like that’s what he’s saying?”

Culturally dependent humor and jokes relying on wordplay are other examples of elements that are difficult to translate well into another language, and when interviewed for a newspaper article on dubbing in 1952, veteran dubbing writer/director Lewis E. Ciannelli spoke of sometimes having to re-write lines completely to create a better effect. “What makes an American audience laugh may leave Italian movie-goers cold, and vice versa,” Ciannelli commented.

These days, a lot of BluRay releases of Italian films include both the English and Italian dubs as well as English subtitles for the Italian track, and if you want to get a good idea of just how much the English and Italian dialogue could sometimes differ from each other, try turning on the subtitles for the Italian audio while you listen to the English dub track. It can make for some very interesting viewing!

Once a dubbing script was completed, dubbing actors had to be cast, and this process was based around a fairly simple principle. “In casting dubbing, the Italian rule prevailed: “voce/volto” (voice/face). In other words, does the voice you selected sound like it’s coming out of the face that’s onscreen?” Ted Rusoff explained in his Video Watchdog interview.

The dubbing directors would hold auditions for new actors, and also sometimes if there were big, important roles to be cast and they were unsure of who to use, but for the most part, the directors were familiar enough with the available talent pool that they simply called on whichever actors they felt would be the best fit.

The next step was the actual dubbing process, which took place in a soundproofed recording room – usually referred to as a sala. The process back in those days was that the film set to be dubbed was physically cut into little lengths which the dubbing director deemed fit (typically around one minute) and then formed into a loop by tying two ends together. At one end of the dubbing sala was a large screen on which the loop was run, and well back from this was a reading stand for the script, and a mike in front of it. The loop would be played over and over on the screen until the dubbing actors felt they were able to catch the rhythms and get their voices in sync with the lip movements of the actors on the screen, while at the same time trying to deliver as good a performance as possible. The dubbing director, who was mainly concerned with the performances and artistic direction, would make various suggestions with each run through, and was assisted by a sync assistant (sometimes also referred to as sala assistant), who was in charge of the technical direction, and who would correct the dubbers if they didn’t get the rhythm or length of each line right.

When the dubbers felt they had the rhythm and sync down, the actual recording process would begin, but it practically never happened that they all managed to nail it on Take 1. It would usually take at least four or five takes to get it right, though sometimes, things could go on for quite a lot longer than that. Very often, this was down to how good the adaptation was.

Dubbing actor Paul Goldfield, when looking back on his dubbing past in a blog post from 2011, stressed how vital a good adaptation is for getting a good end result: “The dubbing script is of primary importance. If done well it’s amazing how well the English words fit into Italian mouths. If done badly... well, we’ve all seen Japanese films dubbed into English.”

Dubbing actress Nina Rootes, who also worked as a sync director and sometimes wrote English dubbing scripts in the early 1960s, found that one of the main challenges involved in preparing a dubbing script was not knowing which dubbers were going to dub the various parts. In her book Adventures in the Movie Biz she writes:

“One sticky point is that some artistic directors are so swayed by the appearance of the dubber – maybe casting a fat guy to play a fat guy – that they don’t always give enough attention to the dubber’s voice. A fat guy may speak very fast, or very slowly, his voice may be light and squeaky or deep and growly. This makes the job of both translating the script for lip-sync – since you don’t know who is going to dub the part – and keeping the dubber in sync during the recording very challenging. A certain amount can be corrected in the cutting room afterwards, you can pull the line up a little or pull it back, but the length will be the same. Of course, I am talking about the Stone Age techniques available at that time”.

|

| Illustration of a recording session in Roman dubbing sala in the 1960s. From a clip of unknown origin featured in the documentary Vogliamo anche le rose (2007). |

Adding to the tenseness in the dubbing studios was the fact that the dubbing crews had very strict time and budget constraints to deal with. Dubbing writer/director John Gayford recalled that dubbing directors would give the producers an estimate of how much time would be needed to finish a dub, and they then had to carefully adhere to the schedule and make sure everything got finished on time, because if they went over the estimate, the difference would come out of their share.

Hectic workdays were something the dubbers quickly got used to, however. They learned to work fast, with some films being dubbed in the matter of a few days, although long, careful jobs – typically reserved for more prestige projects – could take up to two weeks. However, these quick work schedules meant there was usually little to no time for preparation, with the dubbing cast having to tackle whatever was thrown at them head-on.

“The range of emotions sometimes made the work challenging. We had to cry, laugh, shriek, moan, whistle, whisper, etc. High quality performances were demanded,” dubbing actor Dan Keller explained.

“We rarely saw the whole film, and never our own versions. We just had to go in cold and gather what we could of the character from the director and the first loop,” dubbing actress Nina Rootes writes in her book Adventures in the Movie Biz. “People marvel at the skill of film actors, who rarely, if ever, play their parts in chronological order, but they have the script to study months in advance, talks with the director and rehearsals before the shoot starts, at least if it’s a half-ways decent production. And if they are unhappy with their performance in a scene, they can do it again, and again. So pity the poor dubbers. We just looked at the screen and asked: ‘Which one am I?’ and were told, ‘The fat lady on the left, she’s a feather-brained but charming person’. And that was that.”

New actors who wanted to get into the business were auditioned and tested, but dubbing actor Roger Browne recalls there were no classes or practice sessions, because studios cost money, which meant they all had to learn simply by doing.

Yet for all the challenges the dubbing crews had to tackle, there was little to no guidance to be had from the filmmakers, as Italian film directors rarely, if ever, cared much about the English versions of their films. Occasionally, producers would be present in the dubbing salas to supervise and approve of voices etc., but a lot of the time, the dubbers were left to themselves.

“Directors and producers never turned up to supervise,” dubbing director Nick Alexander recalled when interviewed for the book Profondo Argento – The Man, the Myths & the Magic. “You’d think they’d be there, but there was seldom any interest in the process as long as the product was delivered on time.”

The trouble with dubbing English on English

As the Italian film industry kept blossoming throughout the 1960s and producers became increasingly aware of the potential for earning a good profit by exporting quickly made genre films abroad, more and more Italian productions were aimed specifically at the international market. Consequently, it soon became common practice to shoot these films with the actors speaking English on set in order to make the dubbing more seamless. This meant that the Italian dubbers were left with the challenge of dubbing dialogue originally mouthed in English into Italian, but with all the foreign product they were already dubbing, they were very much used to that, plus Italian movie audiences – having grown up with dubbing – are generally much more forgiving of any sync issues than English speaking viewers.

But even though shooting the films in English was meant to facilitate the dubbing process, it was actually the exact opposite that happened.

“Things became a lot more difficult when they started shooting in English, because often the dialogue would have been translated badly virtually overnight and had serious problems,” Nick Alexander recalled in his Profondo Argento interview.

Further complicating the situation was the fact that a lot of Italian actors at that time had very limited grasp of English. Many had to learn their lines phonetically and then delivered them in heavily accented, and sometimes completely indecipherable English – typically spoken in an awkwardly staccato rhythm. Thus, the original English dialogue from the shooting scripts could not be retained, but had to be adapted and fitted as best as possible to the actors’ mouth movements.

“Of course, if you can prepare the actors on set and get them all speaking English with the right rhythms, you can make it look like a live sound picture with careful post-syncing. I did this with a number of films that turned out well,” said dubbing writer/director John Gayford, who served as dialogue coach on the movie sets of several of the films which he subsequently dubbed into English.

Alas, far from all Italian productions had a dialogue coach present on set – especially not the more low-budget films – and so other tricks had to be employed. One of the most famous of these was the use of counting, with actors simply being instructed to recite numbers (be it random numbers, or counting downward from hundred etc.) so that their lips were moving. As usual, ‘fix it in the dubbing’ was the mantra!

|

| Illustration of Italian actors reciting numbers during shooting. Taken from an article on dubbing in the Pittsburgh Press in January 1975. |

So considerable were the difficulties with dubbing English on English that it was reflected in the payment, with dubbing actor Dan Keller recalling that the dubbers were actually paid more money to dub English on English than they were to dub English on Italian.

But it was not only the European actors that had to be dubbed. Since the Italian filmmakers were shooting without live sound, the American or British stars that typically headlined these films also had to be dubbed – often, but certainly not always, by themselves. Stars such as Lee Van Cleef, Henry Silva, Joseph Cotten, Carroll Baker, Lionel Stander, John Saxon and Arthur Kennedy were just some of the faded Hollywood stars that made tons of movies in Italy, and who spent many hours post-synchronizing their own performances in the various Roman dubbing studios. They were not really obliged to do so, however, and – unless they had a specific deal worked into their contracts – they were not paid extra to dub themselves. Many still chose to do it for the sake of their own performance, and not wanting their fans to see them dubbed over by someone else.

In films where an American star is clearly dubbed by someone else, it is therefore tempting to speculate that the reason must be that the actor didn't bother to do his own dubbing because he hated the film, or thought it was so bad it would never get picked up for release anywhere. And while this was undoubtedly the case in certain examples, there could also be far less dramatic reasons behind it, such as unavailability due to the actor in question having moved on to a new project by the time the English dubbing process was ready to start.

Sometimes, it could even be a creative choice. Like in the case of Edmund Purdom, whose performances in the spaghetti westerns The Heroes of Fort Worth (1964) and Gun Shy Piluk (1968) ended up being dubbed by others. As a frequent dubbing actor in his own right, Purdom would have been perfectly capable of post-syncing his own performances, but because these were western films, his distinct British accent was no doubt considered inappropriate, and hence he was re-voiced by American dubbers Tony La Penna (in the case of The Heroes of Fort Worth) and Frank Latimore (in the case of Gun Shy Piluk).

|

| Edmund Purdom found himself being dubbed to make for a more convincing cowboy. |

Except in the rarest of cases, name stars dubbing themselves were always single-tracked, so that they were alone in the dubbing studio with just the dubbing director and the sync assistant. This allowed the dubbing directors to focus all of their efforts on helping the stars do a good job of dubbing themselves, which was no simple task.

“Part of the dubbing director’s craft is to help actors dubbing themselves to recreate their on-set performance, not always easy for the inexperienced. The dark and the mechanics of the dubbing room are a far cry from the all-involving, high-energy experience on the set,” Nick Alexander said of the process in his Profondo Argento interview.

Hollywood actors who worked steadily in Italian cinema grew used to dubbing their own performances, and came to consider it an inevitable part of the whole Italian moviemaking experience, though some came up with strategies to make the process easier on themselves. On the DVD commentary track for the Italian horror film The She Beast (1966), Ian Ogilvy discussed some of the challenges of post-syncing one’s own dialogue and how he always made sure to avoid any “Uh”, “Eh” or other kinds of hesitation noises: “[It] is very difficult when you then later on go into a studio and try and reproduce those little idiosyncratic noises that you made. So I always, when I was doing acting like this, when I knew I was going to post-sync it, I would always try and keep it very simple – to make my life simpler.”

The dubbing personnel

In 1975, there were up to 150 American and British actors working with dubbing films into English in Rome. That’s more than twice as much as the roughly 60 dubbing actors that made up the talent pool back in 1953, and a good illustration of how much the Italian film industry had blossomed and the need for English-speaking voice talent had increased since the 1950s.

But who were these anonymous talents who spent such long, hectic hours in the dubbing salas, trying to match their characteristic voices to the lip movements of the actors on the screen in film after film without ever receiving any credit for their hard work?

Many were actors – some of them very successful ones who simply did dubbing on the side to supplement their incomes; whereas others were newcomers who dubbed while trying to get their big break. Quite a few were singers, musicians or entertainers of some kind, and many supplemented their dubbing incomes through other language-related jobs, such as doing translations, teaching English to Italian actors, or dialogue coaching on movie sets. Some did dubbing while on their way up in their careers; others while on the way down. Nearly all of them fell into dubbing by chance, with some only working in the field for a while before moving on to something else, whereas others would go on to spend the rest of their lives working with dubbing. Common for them all was that they worked long and hard to make thousands of Italian films accessible to a wider audience. Their remarkable voices have enhanced countless performances, and without their hard work, a lot of these films wouldn’t be even halfway as enjoyable!

The big leading men dubbers of the 1960s and 70s were Frank Latimore, Dan Sturkie, Robert Sommer, Bill Kiehl, Ted Rusoff, Michael Forest, Rodd Dana, Frank von Kuegelgen, Roger Browne, Marc Smith, Frank Wolff, Craig Hill, Larry Dolgin, Tony Russel, Larry Ward and Edmund Purdom. The great character actor dubbers were Tony La Penna, Edward Mannix, Richard McNamara, John Stacy, Frazier Rippy, Robert Spafford, Ken Belton, Stephen Garrett, Mel Welles, Michael Tor, Lewis E. Ciannelli, Roland Bartrop, John Gayford, Christopher Cruise, Rolf Tasna, Charles Borromel, George Higgins, Geoffrey Copleston, David Mills, Roger Worrod, Walter Williams, Robert Braun, Marne Maitland, Curt Lowens and Gene Luotto, while other important players were Frank Gregory, John Fonseca, Charles Howerton, Paul Harding Mueller, Hunt Powers (Jack Betts), Alex Rebar, Fred Neumann, Walter Barnes, Donald Hodson, John Steiner, Jim Dolen, Steffen Zacharias, John Kitzmiller, Hal Frederick, Rai Saunders, Robert Lowell, Mickey Knox, Cyrus Elias, Robert Brodie Booth, John Karlsen, Ray Mottola, Robert Andrulonis, Raymond Burgin, Jacques Stany, Colin Webster-Watson, Jay Flash Riley, Clebert Ford, Fred Ward, Thomas Hunter, Lawrence Montaigne, Vic Hawkins, Paul Costello, Dan Galliani, Mike Spaulding, Terry W. Sanders, Burt Nelson, Edward Van Sickle, Marvin Drake, James Mishler, Peter Boom and John Thompson.

| |

| Some of the most famous leading men dubbers. 1: Frank Latimore. 2: Dan Sturkie. 3: Bill Kiehl. 4: Ted Rusoff. 5: Michael Forest. 6: Robert Sommer. |

|

| More great leading men dubbers. 1: Larry Dolgin. 2: Roger Browne. 3: Craig Hill. 4: Rodd Dana. 5: Tony Russel. 6: Marc Smith. |

|

| Some of the terrific character actor dubbers. 1: Tony La Penna. 2: Robert Spafford. 3: Edward Mannix. 4: Frazier Rippy. 5: John Stacy. 6: Mel Welles. |

Of the females, the undisputed dubbing queens were Susan Spafford, Carolyn de Fonseca and Pat Starke, who were all in the business for four-five decades. Other leading players of the 1960s and/or 70s were Silvia Faver, Linda Gary, Geneviève Hersent, Jodean Russo, Sally Amarù, Yvonne Pizzini, Joan Rowe, Carol Danell, Peggy Nelson and Uti Hof. The great character actresses were Cicely Browne, Louise Lambert, Nona Medici, Veronica Wells, Irene Guest, Jan Lowell and Gisella Mathews, and some of the numerous other ladies that worked with dubbing during those years include Lisa Figus, Chrystel Dane, Lucretia Love, Sonia De Dominicis, Tamara Lees, Honora Fergusson, Alice Campbell, Vera Dolen, Joy Cale, Geraldine Catalano, Peggy Olsen, Sara Collingswood, Arianne Ulmer, Audrey Fairfax, Shirley Herbert, Giulia Patriarca, Renée Dominis, Carol Conti, Sandra Kennedy, Sheila Goldberg, Nina Rootes, Denise Carpenter, Ruth Carter, Shirley Douglas, Anita Ardell, Lenor Madruga, Tallie Cochrane, Mickey Fox, Joan Young, Helen Stirling, Nancy Pierce, Nina Matchkaloff, Jane White Viazzi, Joyce E. Meadows, Sylvia Daneel, Moa Tahi, Marisha Vasek, Avril Gaynor and Bettine Milne.

|

| The great leading lady dubbers. 1: Carolyn de Fonseca. 2: Susan Spafford. 3: Pat Starke. 4: Silvia Faver. 5: Geneviève Hersent. 6: Linda Gary. |

|

| Some of the other big dubbing ladies. 1: Peggy Nelson. 2: Jodean Russo. 3: Carol Danell. 4: Uti Hof. 5: Sally Amarù. 6: Chrystel Dane. |

|

| The wonderful character actress dubbers. 1: Cicely Browne. 2: Louise Lambert. 3: Nona Medici. 4: Veronica Wells. 5: Gisella Mathews. 6: Jan Lowell. |

Child dubbers were in short supply, and consequently, adult female dubbers were frequently tasked with supplying voices for both young girls and boys. This produced rather unsatisfactory results, however, and so the dubbing directors would often recruit some of the dubbers own children to do kids’ voices. Two frequently employed child dubbers during the 1960s were Del Russel (the son of Jodean and Tony Russel) and Jodi Lowell (the daughter of Jan and Robert Lowell), and Tony La Penna’s son, Leslie, also occasionally came in to dub young boys. When Del Russel and his parents departed Rome in 1967, the mantle was passed to Dan Keller, who became the male kid dubber of choice until the early 1970s, whereas teenage parts were usually covered by Gene Luotto’s sons, Andy and Steven, and their friend Paul Goldfield, before they eventually graduated to adult roles.

The late 1970s and early 1980s saw the arrival of many dubbers who would go on to make big names for themselves on the Roman dubbing scene, such as Gregory Snegoff, Penny Brown, Russel Case and David Traylor, while other important dubbers who joined in during the course of the 1980s include William Berger, Del Russel, Victor Beard, Dale Wyatt, John Leamer, Bruce McGuire, Mitchell Berkman, Clarissa Burt, Susan Zelouf, Virginia Bryant, Mary Sellers, Martin Dansky, Dina Morrone and Bianca Ara.

Voice talent that made their mark during the 1990s and 2000s include Clive Riche, Larry Kapust, Francis Pardeilhan, Anna Mazzotti, Teresa Pascarelli, Jane Alexander, Sean Patrick Lovett, David Brandon, Adrian McCourt, Mark Thompson Ashworth, Josh Spafford, Eleonora Baldwin, Lawrence McCormick, Vincent Riotta, Leslie Csuth, Robert Steiner, Katherine Wilson, Giulia Bernardini, Flaminia Fegarotti, Katie McGovern, Eddie Zengeni and Mark Hanna.

The dubbing directors from the golden years of dubbing – most of whom also did frequent voice acting – were Gene Luotto, Nick Alexander, Ted Rusoff, Richard McNamara, Tony La Penna, Frank von Kuegelgen, Lewis E. Ciannelli, Robert Spafford, George Higgins, Gino Bardi, Mel Welles, Geoffrey Copleston, John Gayford, Christopher Cruise, Cesare Mancini, Larry Dolgin, Gisella Mathews, Frank Gregory, Tony Russel, Michael Tor, Paul Harding Mueller, Alex Rebar, Mark Salvage, John Crowther, Dom Leone, Alan Thornton and Ralph Zucker.

|

| A few of the great dubbing directors. 1: Nick Alexander. 2: Gene Luotto. 3: Richard McNamara. 4: Geoffrey Copleston. 5: Lewis E. Ciannelli. 6: John Gayford. |

The majority of dubbing directors also did their own adaptations and scripts, but there were also several dubbing scriptwriters who only did scripts and adaptations, and did not direct themselves. Among the notable adaptors only were Ian Danby, John Hart, Edward Mannix, John Fonseca, Frazier Rippy, David Mills and Ruth Carter.

The sync assistants were the assistants to the dubbing directors, and were in charge of the more technical aspects such as making sure the dubbing actors were keeping in sync and getting the rhythms and lengths of their lines down right. Some of the greats in this field were Clementina Luotto, Carolyn de Fonseca, Gisella Mathews, Sonia De Dominicis, John Fonseca, Camilla Trinchieri, Uti Hof, Peggy Nelson, Sheila Goldberg, Delores Devine and Valentino Bruchi.

These lists of names are of course by no means complete. Not even close! But it’s important to keep in mind that with the booming film industry in Rome in those days, the city was practically crawling with hopeful American and British actors, and so many of these found their way into dubbing at one point or another – some, for what turned out to be decades, while others only did it for a short period. As Ted Rusoff put it when interviewed about dubbing in 1975: “Nobody comes to Rome to be a professional dubber. It’s frustrating for good actors to be satisfied with dubbing alone. We use actors who are here temporarily, some singers, and even an architect or two.”

The overall majority of the Rome-based dubbers were Americans, and films were habitually dubbed in American-English in order to appeal to the international market, and particularly the US one, which had little to no tolerance for films spoken in British-English. Consequently, only films with a specifically British settings, such as Double Face (1969), The Weekend Murders (1970), 7 Murders for Scotland Yard (1972) and Let Sleeping Corpses Lie (1974), or certain historically-themed films were dubbed entirely in British-English, and British dubbers were not in great demand.

“We Brits didn’t dub as much as the Americans because it was the US market that the film makers in Italy wanted to break into, so the dialogue was generally more American in style,” British-born dubbing actor/director John Gayford explained in a post in the Facebook group Peplum Paradise in 2014. “I personally felt American fitted far more easily into Italian-mouthed speech patterns and the idioms much easier to adapt than stiff upper lip or regional British accents and expressions. The few of us Brits who did dub tried, often rather pathetically, to come up with accents known as ‘mid-Atlantic’. Of course, Irish or Scottish actors and actresses were far more acceptable and could do good American, a language that largely grew out of the Scottish and Irish immigrants who arrived on Ellis Island with all the Italians and other Europeans about 150 years ago.”

In spite of this, there was a small but stabile group of British dubbers that found themselves working regularly and frequently over many years. In addition to John Gayford, the other prominent Brit dubbers were Edmund Purdom, Ken Belton, John Stacy (originally from Australia), Silvia Faver, John Fonseca, Roland Bartrop, Christopher Cruise, Veronica Wells, Louise Lambert, Roger Worrod, Charles Borromel (Scottish), Chrystel Dane, Geoffrey Copleston, John Steiner, Marne Maitland (Anglo-Indian), Donald Hodson (Australian), John Karlsen (from New Zealand) and Nick Alexander. Some of these dubbers were successful because they were able to convincingly adopt the so-called mid-Atlantic accent that was seen as preferable to most American audiences; others, because it was considered perfectly fine to have one or two supporting characters dubbed with a British accent – just as long as it fitted the type. Types such as old professors, disgruntled chiefs of police and stuffy aristocrats, for example, could frequently be heard speaking in pronounced British accents against otherwise American-English-dubbed characters. This practice of utilizing different accents within the same film was, however, something that a lot of contemporary film critics took much issue with, and it was routinely criticized in reviews.

|

| Some of the Brit dubbers of Rome. 1: Edmund Purdom. 2: Ken Belton. 3: Roger Worrod. 4: John Steiner. 5: Charles Borromel. 6: Marne Maitland. |

It should also be noted that there was a bit of overlap with the English dubbing scene in Paris, with several Paris-based dubbers being called on for occasional dubbing jobs in Rome. Parisian English dubbers who are currently known to have gone to Rome to dub are Jean Fontaine, Bruce Johansen, Barbara Sohmers, Lee Payant, Duncan Elliott, Ginger Hall, Russ Moro, Eric Sinclair, Sally Wilson, Hal Brav, Maggie Brenner and Saul Lockhart, but surely many others as well.

In turn, many of the English dubbers in Rome were also frequently farmed out to other European dubbing hubs, particularly in Spain as per dubbing actor Rodd Dana. “Mel Welles, Mel Gaines, Bob Spafford, Dan Sturkie and I were often flown to Madrid and Barcelona to do dubbing,” Dana recalled. “There were groups who did dubbing at the Chamartín Studio in Madrid and another one in Barcelona. We worked regularly with both.”

One thing that remains a somewhat sore point for fans of the English language dubbers of Rome is the complete lack of acknowledgement for their work in the credits of the films they worked on. Whereas Italian, French, German etc credits will at least occasionally list the dubbing actors, this more or less never happened in the English credits. Which is frustrating not only because it deprives the many hard working dubbing actors of the credit and recognition that they so richly deserve, but also because it makes it all the more difficult and challenging to try to identify the many familiar voices that recur in film after film.

The lack of on-screen dubbing credits was no coincidence, though, but very much a deliberate choice, because the intention was to do such a good job on the dubbing that audiences would be fooled and never even realize that they’d watched a dubbed film. Dubbing cast lists would have shattered any such illusion, and therefore, they were never done, other than in very rare cases such as animated films, or in some mondo documentaries where the narrator would sometimes receive a credit.

Thankfully, at least the dubbing directors are credited from time to time, and sometimes also the recording studios, so it’s always worth paying close attention to the title sequences.

|

| This was usually as comprehensive as English dubbing credits would get. From The Black Hand (1973). |

|

| An example of a fairly detailed English dubbing credit. From Brother Outlaw (1971). |

Not receiving any credit was not necessarily something the dubbers themselves minded, however. Dubbing actor Marc Smith talked candidly on the subject when interviewed for a newspaper article in 1970: “It’s been a perfect job, really, because some of the films and dialog are so bad, I’m perfectly happy to remain anonymous. We say in the business: ‘Take the money and run.’ I can’t complain.”

The dubbing organizations

Throughout the 1960s, the English dubbers in Rome were organized through an unofficial union called the English Language Dubbers Association (ELDA). This union was established in 1954, having evolved from the Anglo-American Dubbing Association that was started by Gisella Mathews and Valentino Bruchi in 1949. The information available on the origins of the ELDA is sketchy at best, but dubbing actors Rodd Dana and Roger Browne both recalled that when they first became involved with dubbing in the early 1960s, the organization was largely being managed by Michael Billingsley and his wife Rhoda, who was basically running ELDA from her kitchen table, holding auditions, casting and assisting the dubbing directors. Eventually, however, ELDA became better organized, and they were able to set up an office with a couple of employees, and charge producers for their service of providing dubbers and scheduling work sessions.

|

| Advertisement for the services of ELDA in Variety (May 12, 1971). |

Actor and dubber Tony Russel served as president of ELDA throughout much of the 1960s, and when interviewed for Video Watchdog in 2007, he recalled that at the time, there were separate English dubbing organizations competing for the same work and cutting each other’s throats by dubbing for less and less money. ELDA was one of these organizations; the other was what dubbing actor Roger Browne describes as a splinter group led by prolific dubbing actor/director Richard McNamara. Each group had dubbers working exclusively for them, and this is why Italian films from the early to mid-1960s always feature the same group of voices paired together. The top dubbers at ELDA during this period were Bill Kiehl, Frank Latimore, Susan Spafford, Carolyn de Fonseca, Stephen Garrett, Jodean Russo and Michael Tor, whereas the biggest players in Richard McNamara’s splinter group were Robert Sommer, Dan Sturkie, Cicely Browne, Curt Lowens, Charles Borromel, John Stacy and McNamara himself.

Tony Russel worked hard to try to get everyone to unite under the ELDA banner, which he finally managed to achieve in the mid-1960s. This was to prove beneficial for most everyone involved, though for Richard McNamara, who had been able to snap up a considerable number of jobs through operating his own group, the amalgamation with ELDA was a bit of a blow. “Dick begrudgingly came along; he would then have to compete with top directors for films,” Roger Browne remembered. “But production went up, as well as quality of work.”

This was around the time of the spaghetti western boom and the golden years of English dubbing in Rome, with a constant stream of internationally geared productions being churned out and promptly dubbed into English for export. These were busy times, and one person who played a key role in arranging, scheduling and making sure everything ran smoothly was ELDA’s office secretary Chris Selheim, who was in charge of manning the phone, assisting the dubbing directors in casting, and making work and payment calls to the dubbers.

“Chris in the office was very helpful in that she had

all the schedules in front of her, knew who was where and when, who was

available or not,” Roger Browne explained.

And having that kind of overview was essential, because there were many different dubbing studios. International Recording and Fono Roma were the biggest and most important studios, but there were many smaller ones as well, and they were spread out all over town. The dubbers had to go wherever there was availability, and that could prove complicated as far from everyone had cars.

“It was five years before I got a VW,” Roger Browne recalled. “I got a bicycle, went everywhere. People used to call me to ask which bus, or buses, to take for various studios since I lived quite central.”

“It was a kind of conveyor belt reality in which we were called on little notice and scheduled for so many turns (a turn was usually two to four hours long), and we were paid according to time spent on a particular film (number of turns) and the number of 'battuta'/lines spoken in each turn,” dubbing actor Rodd Dana recalled.

“When the ELDA lady called to book us for jobs, she told us how many lines (and what type) we were to do, which would give us an idea of how big the job was,” dubbing actor Dan Keller explained.

|

| ELDA credit from The Mask of Satan (1960). |

|

| ELDA credit from Zorro at the Court of Spain (1962). |

|

| ELDA credit from The Tough and the Mighty (1969) |

But while ELDA was highly productive and getting a lot of work done quickly and effectively, the organization was operating under the radar, with incomes going unreported and no taxes being paid. According to Roger Browne, who took over as president of ELDA in 1969, this led to some tricky situations, like when he was robbed coming from the bank with payroll, or when they were ripped off by their accountant and were unable to take him to court due to ELDA not being legal.

|

| Roger Browne, president of ELDA during the late 1960s and early 1970s. |

Eventually, it was decided that it was necessary to make the organization legal and start paying taxes and have money contributed towards the dubbers’ retirement. And so sometime in the mid to late 1970s, ELDA was finally replaced by a new English dubbing organization that carried the name Associated Recording Artists (ARA).

“We wanted to eliminate all traces of ELDA to avoid a paper trail of unreported income,” Roger Browne said of the name change. “We changed offices, and ELDA mail was not forwarded but picked up by our two-person staff who remained.”

Under the new ARA banner, English dubbing in Rome could continue to run smoothly, which it did all through the 1980s, during which time Leslie La Penna served as president of ARA while his wife Claudia ran accounts, scheduling and payment.

|

| Flyer from the early 1990s or thereabouts promoting the services of ARA. |

|

| ARA credit from Odd Squad (1982). |

|

| ARA credit from Women's Prison Massacre (1983). |

Eventually, however, the gradual decline of the Italian film industry led to English dubbing starting to dry up in the 1990s and especially in the 2000s, by which point much of the English voice work in Rome was made up of animation dubbing.

|

| By the 2000s, dubbing work in Rome was made up in large part by animated productions such as Farhat, the Prince of the Desert (2004), featuring several dubbers from the classic years. |

The work done by the dubbers back in the golden days lives on, however, and through this blog I aim to bring many of the anonymous heroes and heroines of English dubbing in Rome into the spotlight by looking closer at their careers and some of their best, most memorable work, which will hopefully bring them some of the recognition and appreciation that they so richly deserve. Stay tuned!

© 2023 Johan Melle

Sources:

Articles:

- “Movies’ Tower of Babel Trick Turns All Tongues to Italian” in Clarion Ledger (May 11, 1952).

- “Europeans Look to the U.S. as Major Film Market” by Albert Ruben, in The Hammond Times (October 22, 1952).

- “Rome Eclipses Paris as New Mecca for American Tourists” in The Arizona Republic (September 13, 1953).

- “Dubbing Foreign Films into English Turning into Big Business in Rome” by Philip S. Cook, in Dayton Daily News (September 20, 1970).

- “Former Isle Radio Figure Dubs Speech for a Living” by Wayne Harada, in The Honolulu Advertiser (October 8, 1970).

- “Rome's

Inner-Colony of Those Trained in Sound-Track Dubs” by Ruth Carter, in Variety (June

19, 1971).

- “In Words of Actors – Italy’s Dubbing Capital” by William Tuohy, in The Pittsburgh Press (January 26, 1975).

- “Titanus Pioneered in Dubbing Films, A Fine Italian Art” in Variety (May 2, 1979).

- “Translating His Talents: Writer Takes ‘Silliness’ to Stage” by Lisa Giguere, in Sun Journal (December 2, 1984).

- “When in Rome, Don’t Trust Actors’ Voices” by Roderick Conway Morris, in The New York Times (December 18, 1992).

- “The

Political History of Dubbing in Films” by Damien Pollard, at www.theconversation.com (July 13,

2021).

Blog Posts:

- “Dubbing Fellini” by Paul Goldfield, at https://paulgoldfield.wordpress.com/ (January 10, 2011)

Books:

- Adventures in the Movie Biz (2013) by Nina Rootes. Umbria Press.

- Passeggiate nel tempo (tra ceroni e microfoni) (2009) by Valentino Bruchi. Pascal Editrice.

Interviews:

- Interview with Dan Keller (2023).

- Nick Alexander interview in the book Profondo Argento – The Man, the Myths & the Magic (2004) by Alan Jones.

- Tony Russel interview “Tony Russel - Our Man on Gamma 1: The Wild, Wild Interview” by Michael Barnum, in Video Watchdog #128 (2007).

- Ted Rusoff interview “Ted Rusoff, il mostro della Fono Roma” by John Charles, in Video Watchdog #159 (2010).

Online conversations:

- John Gayford (2017).

- Rodd Dana (2023).

- Roger Browne (2023-24).

This page was last updated on: February 15, 2025.

This is a wonderful article. My siblings and I were kids who dubbed movies in Rome in the '70s. Yes, I was a girl, but I played a boy - and a possessed doll and a few other roles. It was a unique experience and it is a great story when people ask what my first job was :-)

ReplyDeleteThanks for commenting. That's great and sounds like a lot of fun. I'd love to hear more about your experiences if you'd be interested in that. Just click on my name to go to my Blogger profile and there you'll find my email address.

DeleteThis is a fantastic blog on English language dubbing. One of the directors/dubbers mentioned is my father. I too dubbed a few lines of dialogue in the 80s and 90s. It's so cool that there are so many fans out there of this area of movie history.

ReplyDeleteThank you so much! Very happy to hear that, and yes, I think this is a subject that is of interest to quite a lot of movie fans as there just hasn't been written a whole lot about it.

DeleteI would love to learn some more about your father's work and your own memories of dubbing, so if you're up for helping me out with some information then please either write to me at johanmelle[AT]gmail[DOT]com, or send me a friend request on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/johan.melle.3

Cheers!